Back in 2004 when I was working for a conversation school in Tokyo, a student of mine had an important business meeting coming up with some foreign clients, and signed up for extra lessons so that he might better understand what was going on without having to be completely reliant on an interpreter. The meeting went well, and by way of thanks, he presented myself and another teacher at the school with gifts. Mine was a book called My Encounters With Alaska (「僕の出会ったアラスカ」) by Michio Hoshino (星野道夫), although it took me another six years of studying Japanese to be able to read it.

Fortunately, it’s a book with plenty of pictures, as Hoshino was a photographer who lived in Alaska for many years, before his untimely demise in 1996 at the hands (or rather, at the paws) of a brown bear, while on an assignment for Japanese TV in Siberia .

Perhaps because in some small way it reminded me of my own experiences of living abroad, I found the first chapter of Hoshino’s book particularly moving, and decided to have a go at translating it into English. Having done so, I now realise how little of it I understood on first reading, so if you have any suggestions for improvements or spot any errors in the translation, feel free to let me know (although this is all on a strictly unofficial basis, as I don’t have any kind of permission to reproduce the text!).

(Hoshino’s homepage, incidentally, can be found here.)

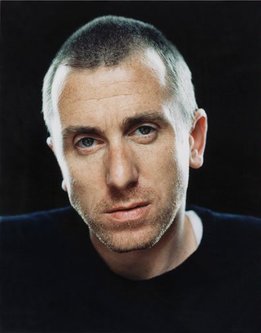

A picture of Shishmaref Village

There was a phone call from Don Ross, the bush pilot.

‘A cameraman from the National Geographic magazine is on his way here. Apparently he’s going to photograph the Caribou migration in the Arctic Circle, so there are a few things he wants to ask you about. Do you think you could go to the hotel for me…? His name is George Mobley.’

The National Geographic deals with nature, geography, indigenous people and history, and it’s the most influential magazine in America. It’s probably the place where photographers want to get published more than any other.

So, a staff photographer from the National Geographic. I bet he’s been all over the world… As I was thinking about this on my way to the hotel downtown, suddenly the name George Mobley began to ring a bell in my mind. Surely not…but it was definitely the same name.

I did a u-turn, went back to my house and took a photography book off the shelf. It didn’t take long to find the page. Next to a photograph that brought back so many memories was written the name ‘George Mobley’. Fancy meeting him in a situation like this…

When I was a teenager, I was fascinated by the nature of Hokkaido, and at the time there were various different books that influenced me. I longed to head north, and before I knew it my thoughts had turned to to Alaska. But I had no clue of the reality – it was only a feeling that grew inside me. More than twenty years ago, there were hardly any books about Alaska in Japan.

One day in the second-hand book district of Kanda, Tokyo, at a shop that specialised in books from the West, I found a photography book about Alaska. On a shelf among many such books, why was my gaze drawn to that one in particular, I wonder? It was as if the book right in front of my eyes was the one that had been waiting for me, and from then on, whether I was on my way to school or going out, that photography book was always in my bag. I read it so much there were finger marks all over it, although in my case, all I did was look at the photographs.

In the book, I couldn’t stop thinking about one page in particular. It was a photograph taken from the air of an Eskimo village in the Arctic Circle. The grey Bering Sea, the leaden skies, the sun shining through a break in the clouds as if through a bamboo screen, the Eskimo settlement like an isolated dot… At first I suppose I was fascinated by the mysterious light in that photograph. Then I gradually started to become interested in the village itself.

Why did people have to live in a place like that, I wondered, at the end of the Earth? The scenery really was desolate. There were no people in the photograph, but you just about make out the shape of what looked like houses. What kind of people could they be, and what were they thinking as they lived there?

A long time ago, while I was absentmindedly gazing out of a train window at a town in the twilight, through the window of a house, I suddenly caught sight of a family sitting around the dinner table. I carried on looking until the light from the window had passed. Then an overpowering feeling welled up inside me. What could that feeling have been? Perhaps that group of strangers was conveying to me the mystery of a life I knew nothing about. Because we were living our lives in the same time and place, there was a sadness about the fact that I would never meet them.

It was a similar feeling to the one I had looking at the photograph of the Eskimo settlement. Somehow or other I wanted to meet those people.

In the caption beneath the photograph was the name of the village. Shishmaref… I decided to write a letter to the village. But who should I address it to? In the dictionary, I found the English word for ‘head of the village’. For an address, all I could do was write Shishmaref, Alaska, America.

‘I saw a photograph of your village in a book. I would like to come and visit. I wonder if there is someone there who will look after me…’

Of course, there was no reply. With no name and no address, how would anyone know who to deliver it to? And even if it had been delivered, there was no reason for someone I had never even met to offer to look after me. I forgot that I had even sent the letter. Then, when more than six months had passed, I got home from school one day to find a letter delivered from abroad. It was from a family in Shishmaref.

‘…We received your letter. I talked to my wife about you coming to our house…summer is the reindeer hunting season. We need a helping hand. …come any time…’

After six more months of preparation, I set off for Alaska. I flew in several small planes and saw animal colonies floating on the ice in the Baring Sea, before the photograph from the book that I had looked at for so long began to overlap with reality, and I pressed my face to the window.

Spending those three months in the village was an intense experience. It was the first time I had seen bears, seal hunting and reindeer hunting, and Arctic nights when the sun never set. Now I was standing in the village from the aerial photograph. I met many people in the course of the trip, and I was fascinated by the variety of ways in which we can live. That summer I was nineteen years old.

After that, I chose to become a photographer, and fulfilled many of my dreams. Then, for the first time in seven years, I went back to Alaska. This time wasn’t to be a short holiday. Three years…no, maybe it would be five years, I thought. The time began to fly by so quickly.

I walked the untrodden peaks and valleys of the Brooks mountain range that traverses Alaska. While kayaking in Glacier Bay, I heard the creaking sound a glacier makes as it moves. I rowed with the Eskimo in their umiak boats as they followed the Pacific whale in the Arctic Circle. I was fascinated by the migration of the caribou, and the trip continued. I recorded the lives of bears through the course of an entire year. I looked up to see the aurora borealis countless times. I encountered wolves. I learned about the lifestyles of many different people… Before I knew it, fourteen years had passed. I had built a house and put down roots in this place.

If that book hadn’t found its way into my hands in the second-hand bookshop in Kanda, I may never have come to Alaska. No, that’s a crazy thought. But if our lives progress through a series of moments, like looking at one’s own reflection in a bell that rings, then life is a limitless series of coincidences.

But of course, I really did look at that photograph, and I really did go to a village called Shishmaref. From then on, as if a new map had been drawn, this different life became a reality. And the person who took that photograph was George Mobley.

I arrived at the hotel, found the room and knocked on the door. Without knowing what I had been thinking about as I made my way there, George smiled through his grey whiskers as he met me.

After a while, when we had talked about the caribou migration, I took out the old photography book and began to tell him the story I have just recounted here. George looked intently at me and leaned in close to hear what I was saying, which made me feel at ease.

‘Well, well… So my photograph changed your life…’

‘Oh no, it wasn’t quite like that, but…it gave me a great opportunity.’

‘So, do you have any regrets?’

Deep in the eyes of this wise old man, I could see that he was smiling kindly.

Life is full of tricks and mechanisms. In our day-to-day lives, despite crossing the paths of countless different people, most of us never even exchange glances. That fundamental sadness, put another way, is the endless mystery of how people come to encounter each other.

And this is the chapter in the original Japanese:

シシュマレフ村の写真

ブッシュパイロットのドン・ロスから電話が入った。

「今、ナショナル・ジオグラフィック・マガジンからカメラマンが来ているんだ。これから北極圏にカリブーの季節移動を撮りにいくらしい。おまえに情報を聞きたがっているんだ。ちょっとホテルに会いにいってくれないか……名前はジョージ・モーブリイだ」

ナ ショナル・ジオグラフィックマガジンは、自然、地理、民族、歴史を扱う、アメリカで最も権威のある雑誌である。カメラマンなら、誰もが憧れる雑誌かもし れない。そこのスタッフ・フォトグラファーか。きっと、世界を駆け回っているんだろうな……そんなことを考えながら、車でダウンタウンのホテルへ向かう途 中、ジョージ・モーブリイという名前が、突然、記憶の鐘を小さくたたき始めた。まさか……でも、たしかにそんな名前だった。

車をUターンさせ、家に戻り、本棚から一冊の写真集を引き出した。そのページを見つけるのに時間かからなかった。懐かしい写真のわきに、小さくジョージ・モーブリイと書かれている。まさかこんなかたちで会うことになろうとは……。

十 代の頃、北海道の自然に強く魅かれていた。その当時読んださまざまな本の影響があったのだろう。北方への憧れは、いつしか遠いアラスカへと移っていた。 だが、現実には何の手がかりもなく、気持ちがつのるだけであった。二十年以上も前、アラスカに関する本など日本では皆無だったのだ。

ある 日、東京、神田の古本屋街の洋書専門店で、一冊のアラスカの写真集を見つけた。たくさんの洋書が並ぶ棚で、どうしてその本に目が止められたのだろう。 まるでぼくがやってくるのを待っていたかのように、目の前にあったのである。それからは、学校へ行く時も、どこへ出かける時も、カバンの中にその写真集が 入っていた。手垢にまみえるほど本を読むとはああいうことをいうのだろう。もっともぼくの場合は、ひたすら写真を見ていただけなのだが。

そ の中に、どうしても気になるたび、どうしてもそのページを聞かないと気がすまないのだ。それは、北極圏のあるエスキモーの村を空から撮った写真だった。 灰色のベーリング海、どんよりと沈む空、雲間からすだれのように射し込む太陽、ポツンと点のようにたたずむエスキモーの集落……はじめは、その写真のもつ 光の不思議さにひきつけられたのだろう。そのうちに、ぼくはだんだんその村が気にかかり始めていった。

なぜ、こんな地の果てのような場所に人が暮らさなければならないのだろう。それは、実に荒涼とした風景だった。人影はないが、ひとつひとつの家の形がはっきりと見える。いったいどんな人々が、何を考えて生きているのだろう。

昔、 電車から夕暮れの町をぼんやり眺めているとき、聞けなたれた家の窓から、夕食の時間なのか、ふっと家族の団欒が目に入ることがあった。そんなとき、窓 の明かりが過ぎ去ってゆくまで見つめたものだった。そして胸が締めつけられるような思いがこみ上げてくるのである。あれはいったい何だったのだろう。見知 らぬ人々が、ぼくの知らない人生を送っている不思議さだったのかもしれない。同じ時代を生きながら、その人々と決して出会えない悲しさだったのかもしれな い。

その集落の写真を見たときの気持ちは、それに似ていた。が、ぼくはどうしても、その人々と出会いたいと思ったのである。

写真のキャプションに、村の名前が書かれていた。シシュマレフ村……この村に手紙を出してみよう。でも誰に?住所は?辞書を聞くと村長にあたる英語が見つかった。住所は、村の名前にアラスカとアメリカを付け加えるしか方法がない。

“あなたの村の写真を本で見ました。たずねてみたいと思っています。何でもしますので、誰かぼくを世話してくれる人はいないでしょうか……”

返 事は来なかった。当然だった。名も住所も不確かなのだから。たとえ届いたとしても、会ったこともない人間を世話してくれる者 などいるはずがない。ぼくは、手紙を出したことも忘れていった。どころが、半年もたったある日、学校から帰ると、一通の外国郵便が届いていた。シシュマレ フ村のある家族からの手紙だった。

“……手紙を受け取りました。あなたが家に来ること、妻と相談しました……夏はトナカイ狩りの季節です。人手も必要です。……いつでも来なさい……”

約半年の準備をへて、ぼくはアラスカに向かった。いくつもの小さな飛行機を乗り換え、ベーリング海に浮かぶ集落が見えてくると、本で見続けた写真と現実がオーバーラップし、ぼくはどうしていいかわからない思いで窓ガラスに顔を押しつけていた。

この村で過ごした三ヶ月は、強烈な体験としてぼくの中に沈殿していった。はじめてのクマ、アザラシ猟、トナカイ狩り、太陽が沈まぬ白夜、さまざまな村人と の出会い……そして、空撮の写真から見おろしていた村に、今自分が立っていること。この旅を通し、ぼくは、人の暮らしの多様性に魅かれていった。十九歳の 夏だった。

その後、写真という仕事を選び、さまざまな夢を抱いて、七年ぶりにアラスカに戻ってきた。今度は短い旅ではない。三年、いや、五年ぐらいの旅になるだろうと思った。時間は矢のように過ぎていった。

アラスカ山脈を横切るブルックス山脈の、未踏の山や谷を歩いた。グレイシャーベイをカヤックで旅しながら、氷河のきしむ音を聞 いた。エスキモーの人々とウ ミアックを漕ぎ、北極海にセミクジラを追った。カリブーの季節移動に魅かれ、その旅を追い続けた。クマの一年の生活を記録した。数えきれないほどのオーロ ラを見上げた。オオカミに出合った。さまざまな人の暮らしを知った……いつのまにか十四年が過ぎていた。それどころか、ぼくは家を建て、この土地に根おろ そうとしている。

あの時、神田の古本屋であの本を手にしていなかったら、ぼくはアラスカに来なかっただろうか。いや、そんなことはない。それに、もし人生を、あの時、あの時……とたどっていったなら、合わせ鐘に映った自分の姿を見るように、限りなく無数の偶然が続いてゆくだけである。

しかし、たしかにぼくはあの写真を見て、シシュマレフという村に行った。それからは、まるで新しい地図が描かれるように、自分の人生が動いていったのも事実である。つまり、その写真を撮ったのが、ジョージ・モーブリイだった。

ホテルに着き、部屋を見つけ、ドアをノックした。どんな気持ちでぼくが会いにきたのかも知らず、彼は白い髭の中に笑みをたたえて出迎えてくれた。

しばらくカリブーの話をした後、ぼくは古い写真集をとりだし、これまでのいきさつ 彼に話し始めていた。ジョージはじっとぼくを見つめながら、耳を傾けちくれた。それがうれしかった。

「そうか……私の写真が君の人生を変えてしまったんだね……」

「いや、そういうわけではないんですが……大きなきっかけとなりました」

「で、後悔しているかい?」

初老に入ろうとするジョージの目の奥が、優しく笑っていた。

人生はからくりに満ちている。日々の暮らしの中で、無数の人々とすれ違いながら、私たちは出会うことがない。その根源的な悲しみは、言いかえれば、人と人とが出会う限りない不思議さに通じている。