Mrs M called me at 5.30 on Monday morning to say that she was at the maternity clinic with okah-san. An ultrasound scan the previous Tuesday had shown that M Jr was swimming in a slightly smaller amount of amniotic fluid than she ought to be, and after another scan on Saturday, Mrs M was told that if it reduced any further, she may have to be induced later in the week. In the event, she woke up on Sunday morning to the oshirushi (literally ‘honourable sign’, although in English we use the rather more literal – and frankly scary – ‘bloody show’), which meant that all things being well, she would go into labour naturally within the next few days.

I took Mrs M to stay with the in-laws on Sunday evening, and we had been advised that unless your waters break, there is no need to panic until the jin-tsuu (陣痛 / contractions) are ten minutes apart. So despite hers starting at 2am the following morning, she managed to have a last-minute shower before leaving the house, and – bless her – waited until a more civilised hour before waking me up.

After stopping off at a convenience store to buy breakfast for okah-san (Mrs M had already been given her first dose of hospital food), I arrived at the clinic at 7.15, where a friend of Mrs M’s was about to check out after giving birth to her second child. She told us that while this one had taken just two hours, her first took thirty-six, so I braced myself for going at least the following night without sleep.

I also called the board of education to tell them that I wouldn’t be going in to work that day, and after being put through by what appeared to be the town hall caretaker (‘There probably won’t be anyone there,’ he said, ‘Nobody turns up until 8.30’), it took a couple of minutes before my colleague S-san realised who I was, and why on earth I was rattling on about babies and contractions.

By mid-morning Mrs M’s were about four or five minutes apart, and for the next few hours, okah-san and I took it in turns massaging her back and making a note of how much time it took before the next one. We had heard that moving around is supposed to help things progress, so I followed Mrs M up and down the corridor, pen and notebook in hand, and stopped every few minutes as she doubled up against the wall in agony (incidentally, if you happen to pass a woman in a maternity clinic corridor, the chances are she will be walking like John Wayne after a particularly long day rustling cattle).

‘Is there any way to stop the pain?’ Mrs M asked a passing nurse.

‘If you stop the pain then the baby won’t know it’s supposed to come out!’ came the reply.

The clinic we had chosen practices what is known as shizen-bunben (自然分娩 / natural childbirth), although don’t be fooled by the name, as instead of a birthing pool in a candlelit room, natural childbirth in Japan means not being able to receive any form of painkilling treatment (before we emigrated, there was an excellent fly-on-the-wall documentary on British TV called One Born Every Minute, and as well as the occasional epidural, almost all of the mums who appeared in the programme were puffing on gas and air like stoners on a bong).

‘From what I can tell,’ continued the nurse, ‘you’re on course to have the baby today. But you shouldn’t walk around too much. Get some rest in case nothing happens until halfway through the night.’

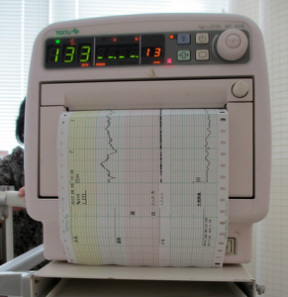

At one point Mrs M’s bump was hooked up to a heart monitor, and we listened as M Jr’s heart rate climbed to around 150 beats per minute mid-contraction, and slowed to around 130 the rest of the time. Towards the end of the test, W-sensei – who I had met on several previous occasions – turned up on his morning rounds.

‘The baby’s fine,’ he said after looking at the readout. ‘Have you mastered Japanese yet?’

‘Not quite yet, I’m afraid,’ I said.

While Mrs M was busy dealing with her contractions (she described them as feeling like really severe period pains), to be honest, I was getting thoroughly bored. When I wasn’t on massage duty, I watched the queue of newborns waiting to be bathed in a big butler’s sink, and wasted time testing exactly how sensitive the motion-sensitive lighting was in the gents’ toilet, re-coiling the cable for the emergency call button, and watching the Olympic highlights on TV (the previous night, Bolt had won the 100m, Murray had won the tennis and Uchimura had won Japan’s second gold medal in the gymnastics). Mainly to get some fresh air, at about three in the afternoon I went on a snack run to the 7-11 – you wouldn’t have known it in the clinic, where most of the blinds were drawn and the air conditioning was running, but it was the first rainy day after weeks of blazing sunshine.

While the interval between Mrs M’s contractions had finally come down from four or five minutes to more like two or three, she was still six centimetres dilated, and more out of hope than expectation, asked one of the nurses to examine her. When Mrs M stood up, I noticed bloodstains on her gown and on the bed, and after a minute or two in the examination room, the nurse re-emerged with slightly more urgency than before.

‘How dilated is she?’ asked her colleague as they jogged back to the examination room for a second look.

‘Eight centimetres. Well, maybe a bit less.’

‘Are you the father? Put this on,’ said the nurse, and held an open-backed white gown in front of me, as Mrs M was led into what looked for all the world like a store room.

Yet more nurses appeared – one of them looked so young that I could have sworn she was one of my junior high school students on work experience – and a woman I assumed to be the midwife put Mrs M’s feet in stirrups and told her to grab hold of the metal bar above her head. A drip was fitted to her right arm and another heart monitor to her bump, and when the next contraction came (by this point M Jr’s heartbeat had begun to slow down rather than speeding up during the contractions), the nurse told her to push.

‘Good, good. You’re doing really well. I can see the top of the baby’s head.’

After nine hours in which practically nothing had happened at all, everything was kicking off, and for probably the first time in my life, I found myself speechless. I wanted to give Mrs M some words of encouragement, but apart from a whimpered ‘Ganbaré!’ (‘Good luck!’), couldn’t think of anything to say in either Japanese or English, and held onto the metal bar almost as tightly as Mrs M.

‘Take off my glasses,’ she said, and one of the nurses was ordered to take them away for safe keeping. ‘No!’ said Mrs M. ‘Don’t do that! I won’t be able to see the baby!’

After ten or fifteen minutes and six or seven pushes a different woman took charge, and this time it was the real midwife.

‘It’s too narrow,’ she said. ‘I’m going to have to give you an éin-sekkai (会陰切開 / episiotomy).’ Which she promptly did, and a couple of pushes later looked at me and said, ‘Do you want to see the baby coming out?’

‘Er, sorry. I’d rather not if that’s OK.’ (I’ve never been one for blood and guts, and in any case, I probably would have keeled over altogether if I let go of the metal bar).

‘Get your hand out of the way!’ said Mrs M, whose hair I had been stroking in a vain attempt at being supportive, and with one more push, M Jr was out.

‘My word, your baby’s got a big bottom!’ said the midwife.

M Jr was as purple as a London 2012 advertising hoarding and covered in blood, and once her throat had been cleared, she let out her first, tentative cry.

Ironically enough, now that the ‘natural childbirth’ was over, it was finally OK for Mrs M to get some pain relief, and she was given a local anaesthetic before the midwife stitched her up. As we had been led to believe, this was possibly even more painful than the birth itself, so that when Mrs M held M Jr for the first time, her expression alternated between a euphoric smile and a gritted-teeth grimace.

After posing for a commemorative photo, I took M Jr outside to meet okah-san, who appeared to be completely unruffled by the whole experience, whereas I was dizzy, red-eyed from crying and had a line of snot dribbling onto my top lip.

‘This is your granny,’ I told M Jr.

‘I’m not a granny,’ said okah-san. ‘I’m the mother’s mother!’

Back in the delivery room, M Jr had a quick first go at breast-feeding before being placed in this elaborate looking cot. Among other features, a heating element kept M Jr at just below thirty-seven degrees centigrade: body temperature, obviously, but also the kind of conditions she will soon have the pleasure of experiencing on a summer’s day in Japan.

The delivery room would soon be needed for another birth, so once a half-litre bag of glucose had emptied into Mrs M’s arm, she was very carefully transferred to a wheelchair and taken back to meet otoh-san and onii-san, who had driven straight to the clinic after finishing work.

Not long after she became pregnant, Mrs M got rather angry when I told her that to be completely honest, I don’t think babies are particularly cute – as everyone knows, they tend to look like a cross between Winston Churchill and Gollum from The Lord Of The Rings.

OK, so perhaps I’m being a little unfair, but M Jr did look as if she’d gone the proverbial ten rounds with Mike Tyson: her eyes were swollen half-shut and filled with sticky, milky tears, her face was puffy, her hair was matted and her mouth was stuck in a kind of exhausted pout.

An hour or two later she was a little more normal – cute, even – although as I stood in the corridor looking at the most recent additions to the population of Ibaraki, I realised that whether they’re Asian, European or a mixture of the two, new-born babies are almost impossible to tell apart. Presumably for this reason, I had been asked to write M Jr’s name on her legs in black marker pen – first name on one leg, surname on the other – and to further aid with identification, the boys were given blue woolly hats and the girls pink ones.

Still, whether or not she looked like a bloke after a boxing match, M Jr had arrived. 50cm tall and weighing 3.26kg (that’s almost 7lbs 10oz in old money), she was born at 4.21pm Japan time on August 6th 2012. Mrs M had been in labour for just over fourteen hours, and we were all safely tucked up in bed again by about ten o’clock on Monday evening.

Congratulations….to you all… oooh so graphic Tom felt as if I was there! Kept my attention till the end! Enjoy being parents x x

Thanks Zoe! (And apologies for the graphic stuff – I should have given it an 18 certificate!)

Brava!! And an episiotomy….eeech.

Did anyone else comment that the last picture shows a baby in a blue hat? Are you sure that’s your kid?? 😀

It is actually a pink hat – it’s just, er, a rather pale shade of pink. Under flourescent lighting. I think.

Episiotomies are very much the rule rather than the exception over here, and seeing as they’re not standard practice in the West these days, it makes me wonder how they go about things – does the mother have to push harder, or for longer?

Congratulations! Thats just awesome! Many pink cigars and toasts all around.

Thanks, Benjamin! I have been smoking at least one pink cigar every day since M Jr was born, and eating toast every morning for breakfast! (That was what you meant, wasn’t it?)