In the autumn of 2005, I was living in Mito, Ibaraki Prefecture. I had just returned from the cycling holiday that will soon become my first (perhaps only?) travel book. I still had a fixed-line telephone in my apartment and one weekend my mother called. She had, she said, been to the doctor after experiencing stomach pains for the past few months. The doctor had scheduled a biopsy and she was awaiting the result. When she called again a week or so later, she had received the official diagnosis: it was liver cancer.

“It feels like it’s happening to someone else,” she said, and at the time, I did not really understand what she meant. Even now I am not sure that I understand; perhaps I never will unless the same thing happens to me.

What she did not mention was that the doctor had given her between six and eighteen months to live. She died almost exactly a year after that first phone call, by which time I had returned to the UK to look after her. Even subsequent to those initial phone calls, the subject of whether or not the cancer was terminal and if so, how long she might have left to live, never arose between the two of us. Partly because of this, partly because of my own naivety, and partly because I was in a state of denial, somehow the fact that she would die did not enter my mind. And when she did, it came as a shock – as if there was always a possibility that she might have beaten the cancer and cheated death.

At the end of 2005, I flew to the UK for about ten days of the Christmas holiday. My mother was, I think, already undergoing chemotherapy and had begun to look frail: she had lost weight and was not going out as much as before. After a few days at her house in Somerset, I planned to return to London and meet friends, but when we talked about this, she asked me to stay in Somerset for longer, and I remember that she cried. Even so, I insisted on going back to Japan for a further three months, so that I could finish my teaching contract and spend more time with my girlfriend, with whom my relationship was going so well that she planned to apply for a student visa and for us to live together in London.

Going back to Japan was, I now realise, a selfish thing to do, but again, I was in denial and did not know or want to believe that my mother would die sooner rather than later. When I left Japan for good in April 2006, I moved to Somerset to live with her – partly, I think, because I felt guilty for delaying my return to the UK, although I also had nothing in particular planned, no desire to return to the job that I had been doing before I emigrated in the first place, and agreed with my brother to do my “shift,” as it were, of looking after her while he was busy with his own teaching job in the Midlands.

During those last few months in Japan at the beginning of 2006, I had a brainwave, and this time it was not born of guilt but a genuine desire to do something nice for my mother. In fact, I probably would have done it even if she had not been ill.

When I was a child, my mother had introduced me to the work of Hokusai, the world-famous Edo-era printmaker, and in particular his Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji and One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji. Ever since I moved to Japan, I had been obsessed with the idea of seeing Fuji and found that in modern-day Tokyo – even in the mountainous, sparsely populated area to the west that is still within the city’s borders – catching sight of it was a much rarer occurrence than it had been in Hokusai’s time. What I did discover was that the sky over Japan tends to be clearer in autumn and winter. If I get the chance, I thought, I should travel to Fuji, photograph it, and produce some kind of tribute to Hokusai as a present for my mother, whose sixty-eighth birthday was to be on 3rd March 2006.

On Friday 27th January, I finished work at 2.30 p.m. and drove straight from the school where I worked to the nearest expressway interchange. With no easy route all the way to Fuji by expressway, I spent an hour or so battling the rush hour traffic on the streets of Tokyo, and arrived at a restaurant near one of the Five Lakes (I cannot remember which, but either Kawaguchi, which is the most famous, or Yamanaka, which is the largest) at 8 or 9 p.m. When I asked the owner if he knew of a cheap place to stay, I was directed to a nearby business hotel.

Excited about the following day, I did not sleep well and woke earlier than I had planned. My idea was not so much to produce thirty-six or one hundred photographs of Fuji, as to document one day in its environs, from the moment that dawn broke to the moment that darkness fell. The hotel appeared almost empty and I assumed that I would be the only person braving the early morning cold, but how wrong I was! The lakeside was positively swarming with photographers – mostly men, mostly old-age pensioners, and with tripods, lens bags, and weatherproof clothing – not to mention ice fishermen and various other Fuji-watching day trippers.

It had been dark when I left the hotel. When I arrived at the lake it was getting light and about an hour later, the morning sun cast the summit in a soft salmon-pink glow.

I spent the rest of the day driving around in search of interesting angles and suitable spots from which to photograph Fuji. I framed the summit – that iconic summit dwarfed by a great wave in Hokusai’s most renowned work – in bus windows, cranes on building sites, and the rollercoaster at the Fuji-Q Highland theme park; between houses, trees, and billboards; and with swans, photographers, and people picnicking on the lake’s frozen surface.

There was hardly a cloud in the sky all day and the only times I stopped to relax were at a roadside services, where people were filling containers with free spring water from a tap in the car park, and for an hour or so at a hot springs (quite by chance, I had visited the same hot springs with a Japanese friend more than a year earlier; on that occasion the weather had been cloudy and we had not seen the summit at all). At one point, I had to recharge the battery on my digital camera using the electrical socket above the sink in a public toilet, where I also took the opportunity to download the photos I had taken so far onto the clunky old laptop that I had brought with me.

By about six o’clock in the evening, the sun had set, the sky had faded from blue to black, and street and house lights on the opposite shore were reflected in the lake.

As the temperature once more began to fall below zero – if I remember rightly, that morning it had been minus-eight before the sun rose – I rejoined the expressway and headed back to Ibaraki. I stopped for an anonymous evening meal at a family restaurant in Tokyo, balanced my phone on the steering wheel to video the long semi-tunnel through which the Jōban Expressway passes as it moves from the Tokyo suburbs to the Ibaraki countryside, and was back at my apartment not long before midnight.

My car was a Suzuki Wit and what is known in Japan as “yellow plate”: that is, one with a yellow number plate and an engine of no bigger than 660 cc, for which road tax, insurance, MOT, and so on are cheaper than larger “white plate” cars. Already years old, it was rented via my employers from a family business in Mito and not exactly the most reassuring vehicle to drive. The Monday after I went to Mt. Fuji, the Wit had what I thought was a flat tyre. When I took it to a tyre shop, they said that it was not a puncture and simply needed reinflating, but what if the tyre had gone flat on the expressway – in the dark and in the mountains – or in a traffic jam on the way through Tokyo? I might have been stuck for hours or not have made it to Fuji at all. More importantly, the car was only insured to be driven in Ibaraki Prefecture. If I had been in an accident or been pulled over by the police – for instance, while ignoring a stop sign, going over a level crossing without stopping, or making an illegal U-turn, all of which I have subsequently received fines and points on my licence for – the trip would have acquired an extra dimension of difficulty and my day of photography quite possibly postponed.

But the stars aligned and I had several hundred photographs from which to choose. I bought a couple of stylish-looking, ring-bound, brown-paper-and-card notebooks from Muji, printed out two each the best twenty or thirty photos, and compiled my own version of Hokusai’s Views of Mt. Fuji in a limited edition of two. One was for my art teacher from sixth-form college and one for my mother. It was probably the first birthday present I had given her in several years, and it was to be the last.

My mother was a complex character. Intelligent and academically inclined, she was the first person from her family to go to university. Her father was an electrician, who among other things had worked on the lighting on Clifton Suspension Bridge (we still have a few vertigo-inducing photographs that he took while climbing it), her mother was a housewife, and both came from poor families of coal miners in the Forest of Dean. My mother was also gifted with languages and the only time she ever left the British Isles was to study in France – in Paris and for several months, I think, although I never found out the details.

She married in the mid-sixties, but her husband suffered from depression and not long after they separated, he committed suicide. When I was younger, she told me that he had died in a car accident – presumably so as not to shock or traumatise me – and after her death, I found the coroner’s report among her possessions. Apparently, she had gone to stay at the house that he was sharing in Oxford. He went to bed, she slept downstairs, and in the morning he was found hanging from the curtain rail in his bedroom. It may have been my mother who found the body, although even if it was not, this was surely an experience that changed her forever.

Her marriage to my father did not last much longer and their separation proved to be the defining moment in my own life. She told me that she had said to him on their wedding night that the marriage would not necessarily last, and this struck me as a very cold – even heartless – thing to say. Although the same is true of every couple, stating as much openly and from the outset was tempting fate, and set the marriage off on the wrong foot.

My parents never officially divorced, and so as not to go through the stress and expense of court proceedings, discussed their separation with a mediator and came to an agreement about child support payments and visiting rights. I was only three or four years old, so am not sure of the exact chain of events, but I believe that my mother had a new boyfriend at the time. During one of my father’s less endearing, less sober episodes, he implied that the boyfriend was the cause of the split, or that my mother was already seeing him before the marriage ended. The boyfriend — at least I assume it was the same man — came to stay at the house to which my mother, brother, and I had moved, and apart from his long ginger hair, the only things I remember about him were that he walked around indoors barefoot and that one of his toenails was rotten, or infected, or had turned black from having dropped something on it or stubbed his toe.

That boyfriend was to be the first of many that my mother had as my brother and I were growing up (my father also had girlfriends, but never introduced any of them to us). Some were very nice, some I was indifferent to, and some were merely unsuitable. There was the married man who used his evening jogs as an excuse to pop round to our house; the divorced father of two that a friend of ours condemned as a “jogging Christian” (my mother had a fondness for beards and the only reason she went out with the jogging Christian was, as far as I could tell, because he had a beard); the leather-jacketed media type who wore far too much aftershave, the younger man; the even younger man; and the warden who wooed her while we were staying at his youth hostel in Wales, then dumped her because he could not find anyone to feed his pet goat while he was visiting us.

So during our teens, when my brother and I should have been dating girls, it was my mother who was gadding about, receiving love letters and phone calls, and going through traumatic break-ups and last-ditch reconciliations. I will be honest and say that if anything, this fucked me up even more than the fact of my parents having separated in the first place. Of course, there were times when I wished my mother could maintain a long-term relationship, even have one of her boyfriends move in with us so that I might have a male role-model in the house (the youth hostel warden was the most suitable that she found over the years and for a brief period, this did seem to be a possibility). It is also a shame that my father revealed nothing about his own love life, as I would have been pleased to know that he was not lonely; that he, too, had his fair share of romance.

But those things never happened and conversely, rather than escaping the rather twisted, unsettled environment in which I grew up, I took a year off after sixth-form college and an arts foundation course, and that one year turned into four. I idled away my time watching videos, watching TV, playing snooker, collecting records, and while my mother progressed through her series of relationships, completely failing to find a girlfriend of my own. Even though I did not want to be, I had turned into a mummy’s boy, still living at home in his early twenties and hanging out with my mother’s friends as much as I did with my own.

On the other hand, my mother had spent much of my childhood ignoring my brother and I. Well, perhaps it is an exaggeration to say that she ignored us, but for much of the time that she might have spent at home, she was busy doing her own thing. This centred around political and charity work – in particular for the Labour Party, CND, and Amnesty International – and involved her standing for election or working as a councillor (mid-Devon being a Conservative Party stronghold, she only ever won a seat on the town council when there were the same number of candidates as vacancies), joining PTAs (not at the schools that my brother and I attended, but as a political representative at others), and campaigning on behalf of her Labour Party “comrades,” as they often called each other. She was a socialist and a left-winger, enamoured of Tony Benn, Ken Livingstone – both of whom I went with her to see speak – Michael Foot, Dennis Skinner, and others like them, but not of sell-outs like Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair, although she was grudgingly pleased when the latter brought to an end so many years of Labour as the opposition party. She was fiercely – even fanatically – opinionated, with an unwavering conviction that she was right, that socialism was right, and that reactionaries and conservatives were wrong.

“Sometimes I honestly think there’s something wrong with them,” she once said to me. “That they’re less intelligent.”

She would tut whenever Margaret Thatcher or one of her Tory minions was speaking on TV, and talk back to them, newsreaders, or commentators when she disagreed with what was being said. Her us-and-them mentality, with Tebbit, Heseltine, Thatcher, and Ronald Reagan as the Bad Guys and left-wingers as the Good Guys, was instilled in my brother and I, who were often left alone in the house when she went to Labour Party, council, CND, or Amnesty meetings.

It is my theory that this obsession with political and social issues stemmed from the experience of losing her first husband in such traumatic circumstances; that it was a way of masking the pain and something to devote her time to that involved not emotional but ideological commitment. I still agree with much of what she stood for, but in recent years it has become clear to me that I myself am too opinionated and argumentative, and that this has, at times, harmed my friendships and relationships. (This realisation has happened in large part thanks to living in Japan, a society in which people do their best to avoid conflict and will go so far as to lie about – or at least conceal – their true opinions in order to maintain social harmony.)

At the age of twenty-three, when I finally mustered some motivation, made a short film, and was offered a place at film school in London, I reacted by distancing myself from my mother emotionally as well as physically. By my early thirties, I remember feeling satisfied with the fact that it had been so many weeks or months since I last talked to her on the phone or visited her in the West Country. I am sure that she was proud of the fact that I had become more independent and was making a life for myself away from home, and as usual, she had work, boyfriends, and politics to keep her occupied. But she must have missed me, too, and particularly because she was diagnosed with cancer as a sixty-seven-year-old and passed away at sixty-eight, I now wish that I had been more attentive. By way of illustration, during one of my visits she gave me a late birthday present. It was a CD by a blues singer called Eric Bibb, but I said to her quite bluntly that I was no longer a fan of blues music and was not particularly interested in listening to it.

My knowledge of psychology is limited, but in line with Philip Larkin’s poem This Be The Verse, for a long time I blamed my parents for my problems: for my social ineptitude, shyness, loneliness, introversion, depression, and lack of motivation. What is more, I blamed my mother more than my father, even though they both filled me, as Larkin puts it, with the faults they had. My father was shipped off to boarding school at a very young age, which I assume is why he became shy, lonely, introverted, and lacking in motivation. My mother, though, came from what appeared to be a conventional, stable, and happy family.

While I was living with my mother for the six months or so between returning from Japan and her death, I busied myself with mowing the lawn, painting the garden shed, redecorating the house, doing odd jobs for her friends and neighbours, and travelling to London. I also began writing: a mostly anonymous blog about my mother’s illness, life in the even smaller town to which she had moved after I went to university, the time I had spent in Japan, and whatever else came to mind. I felt a mixture of emotions and motivations during that time: a sense of duty and of filial piety; and a sense of relief and security that I was back on British soil and surrounded by that which was culturally familiar. Also, if I am honest, I felt impatient, in the sense that because my girlfriend was due to arrive from Japan the following spring, I wanted my mother to hurry up and recover, or for my brother to come and care for her instead, so that I would be free to return to London.

I did not spend much time with my father in the years before he died of cancer, which is something that I now regret. And while I did spend time with my mother in the months before she died, that does not mean that I have no regrets about her. Thanks to being a little older and a little wiser than the last time we had lived under the same roof, our relationship was better than before. I did not shut myself away in my bedroom, she did not disappear to campaign with her comrades, and we were able to talk more openly than in the past. On a practical level, now that I had learned to drive, I could also take her out: to a council meeting; to the opening ceremony for a monument in the town square; to an exhibition of etchings in a village church; to look at the sea on a chilly day, through the car windscreen and while sipping tepid tea from polystyrene cups; to friends’ houses for lunch; to Taunton to trawl the charity shops (there she tried on and bought a dress that she would never wear, to add to a collection of clothes that filled several wardrobes, and that I would later donate to Oxfam in countless black bin bags).

Many people dropped in at the house and many more telephoned to enquire after her welfare. On one occasion an aunt and uncle visited for the day from Wiltshire, and for dinner I cobbled together a rather inauthentic attempt at Japanese cuisine. Because my mother could not move around very well, I waited on her. At one point she asked me to find an old photograph album, but the request came out more like an order and it was an awkward moment. After my aunt and uncle had left and while I was sitting at the computer writing my blog, my mother stopped at the dining room door before she went upstairs to bed.

“I’m sorry about earlier,” she said. “That was a bit rude of me. It’s just that I got a little carried away with myself because your aunt and uncle were here.”

“That’s OK,” I said. “I still love you.”

We were at opposite ends of the room and did not move to hug or kiss each other, but I had surprised myself with my own words. I had never before told my mother that I loved her, and while it felt natural and honest to do so, it felt inadequate, too, and emphasised the fact that I should have done so before. I also felt regretful: that at the same time as expressing my love for my mother in words, I was unwilling to express that love physically.

By the same token, I am not sure that my mother ever told me that she loved me, or at least, not often enough for me to remember it. Particularly when I was a teenager, I tried my best not to display my emotions or to express any kind of affection for my parents. But she, too, could be emotionally detached and not the sort of person who invited displays of affection. Another memory from my childhood is of watching the film E.T. together. Towards the end of the film, when E.T. has been captured by the authorities and is close to death, I noticed that my mother was crying and I remember thinking, “Wow, so she does have a heart after all!”

Perhaps finding that coroner’s report into her first husband’s death was the moment that finally enabled me to forgive her: for the faults she had filled me with and for her prioritising boyfriends and politics over her family. Reading that description of the events in Oxford in the mid-sixties – a description that was so neutral, so shocking – allowed me to see that my mother, too, was human. That, like me, she had experienced unhappiness in her life and that there was a legitimate reason for her shortcomings as a parent. Now that I, too, am a parent, I also understand how hard and what a great responsibility it is. No parent is perfect and nor can they be, and it was wrong of me to expect that either my mother or my father could be perfect themselves.

By British standards, the summer of 2006 was hot and sunny. The garden at my mother’s house was blooming with flowers, the countryside was green and pleasant, and I loved to drive or cycle along the roads in and around the Exmoor national park. One day – probably while I was stripping wallpaper or painting the walls, with the furniture moved to the middle of the living room and covered in old bed sheets – the subject arose of my Views of Mt. Fuji.

“Thank you very much for the photos,” said my mother. “They were really nice.”

“Oh, it was nothing, really. It just came to me one day that it might be an interesting idea to do a kind of Hokusai tribute.”

“Still, it must have been quite an undertaking.”

In contrast with my rejection of the birthday present my mother once gave me, she was genuinely grateful and surprised that I would go to the trouble of creating a photo book for her. And I, too, should thank her: for all of the presents she gave me over the years, whether I wanted them or not; for the fact that she gave birth to me and brought me up – mostly single-handed and while working as a librarian to pay the bills and to keep my brother and I clothed and fed. I should also thank her for introducing me to Japanese culture – while I was still in my teens and when manga, anime, sushi and so on were unheard of in the UK – and to Mount Fuji, of which I am in awe to this day.

The most recent occasion on which I saw Fuji I was with my son. We were driving to Tochigi Prefecture to collect an exercise bike that I had purchased online. From an overpass on Route 50 somewhere near Shimodate, I saw the snow-clad peak on the horizon, a brilliant white in the early morning sun. I pointed it out to M Jr. II and we spent the next few minutes trying to catch sight of it again between the buildings and trees at the roadside. I was as excited, impressed, and inspired then as the first time that I saw Fuji, from the cable car station on Mount Tsukuba during my first visit to Japan, and on the precious few occasions that I have seen it since: from a mountaintop in Nikkō, from a top floor bar in the centre of Tokyo, from the bullet train on the way to Nagoya, while climbing to the summit in the late summer of 2004, and while photographing it from beside a frozen lake on that cold morning early in 2006.

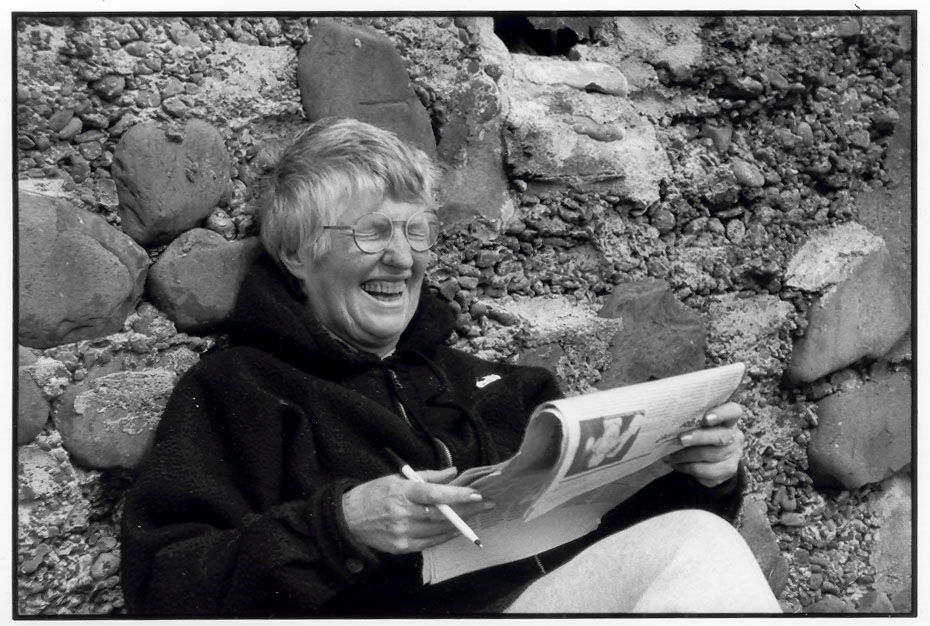

If my mother were still alive, she would have celebrated her eighty-third birthday on 3rd March this year. Below is one of my favourite photographs of her: part-way through a walk in the countryside, doing the Guardian quick crossword, laughing, and happy.