A couple of weeks ago I had a moment of enlightenment, or satori (悟り), as they say in Japanese. At the time I was sitting on a mossy rock, next to a pool of water, in a forest, on a mountaintop, on a cold, damp night, in the pitch dark, and with a plastic bottle in my hand. If you’re wondering how such an unlikely set of circumstances led to a transcendental experience, allow me to explain.

Ask most of its residents what is the highest mountain in Ibaraki Prefecture and they are likely to say Tsukuba, when in fact the correct answer is Mount Yamizo (八溝山 / literally ‘eight ditches mountain’). Yamizo straddles the border with neighbouring Fukushima in the far north of the prefecture, and while it may lack the attractively pointy profile of Tsukuba – not to mention its cable car – it is 145 metres higher and boasts a paved road all the way to its summit.

Noticing this on my dog-eared old Mapple road map one day, I worked out that it would be possible to cycle to Yamizo from our apartment, camp out for a night, get up early to see the sunrise and then cycle back the following morning.

My cycle tours in Japan have been getting progressively shorter over the years – six weeks in 2005, five weeks in 2008 and ten days in 2011 – and with a one-year-old daughter and a son on the way (apologies if this is the first you’ve heard – I was going to write a ‘Mrs M is pregnant again!’ blog post but never got round to it), this seemed like a good idea for a final tour before I become so busy changing nappies and mixing formula that I never have time to leave the house again.

So having negotiated with Mrs M for permission to abandon her and M Jr for the weekend, I set off at 8.30am Saturday 2nd November, when the weather was warm, the autumn colours were just starting to show, and Route 118 between Mito and Daigo Town was busy with sightseers.

As well as the Fukuroda waterfall (袋田の滝), Daigo is famous for its apples, and in the orchards that lined the way the trees were weighed down with large, ripe, red and green ones (in order to make the apples as large, ripe, red and green as possible, silver sheets are placed on the ground to reflect extra sunlight from beneath them).

The woman behind the counter at Daigo tourist information centre said that a campsite marked on the Mapple as being close to the summit of Yamizo had long since closed for business, and I told her that I would probably nojuku (野宿 / sleep rough) instead. While she was a little surprised by this, I reasoned that, in the same way mountaineers do before they set off on a climbing expedition, it would be a good idea to tell someone where I was going in case I got into trouble.

At a crossroads on Route 118 not far north of Daigo there is a road sign showing the way to Yamizo, along with a family-run convenience store the woman at the information centre had said would be my last chance to stock up on supplies for the night ahead. Among other things I purchased their last three onigiri (rice balls), and had a steaming hot bowl of soba at the very small – and very cheap – noodle restaurant next door.

Route 28 winds its way through a succession of small villages in the Yamizo River valley, and past farms whose main crop – where precious little land is level enough to accommodate rice fields – is green tea. A dog out for a walk with its owner barked suddenly as I cycled past, straining on the end of its lead to try and take a bite out of my tyres, and a stooped old lady in Wellington boots, a bonnet and a pinny stopped me for a chat, telling me to ‘Ganbarina’ (頑張りな / ‘Do your best’) about five times before she let me carry on up the road.

There were, as it turned out, a couple more places to buy emergency rations, but they were old-style village shops that sold very little in the way of fresh produce. Again I thought it best to let some of the locals know that a strange foreigner would be camping out on the mountain that night, so engaged the shopkeepers in conversation, and came away with two over-ripe bananas, a tomato and a tube of Smarties for my troubles.

Just as one of the shopkeepers had described it, the road up the mountainside was marked by a large wooden torii (鳥居 / shrine gateway).

Along with this little fellow dispensing free spring water.

Knowing that I would have a long time to spend on the summit with nothing to do, I had made a point of dallying on the way, and reached the torii at three in the afternoon. In theory this left me with just about the right amount of time to get to the top before darkness fell, although in practice it is much, much easier to cycle uphill first thing in the morning when one’s legs are fresh, and the shape of this two-day tour gave me no alternative but to tackle its most arduous stretch in late afternoon.

From being on the gentle slope of Route 28, I suddenly found myself on a 13.5% incline (that’s about 1 in 7 in old money), which aside from a couple of brief interludes where the road levelled off, barely let up for the entire 8km to the top, and around what felt like several hundred hairpin bends.

Actually there were more like twenty-five, but I was constantly weaving back and forth in an effort to find the line of least resistance – ie. the line of least steepness – and to say that my lungs felt as if they were bursting out of my chest would be an understatement: rather, it felt as if all of my major organs were about to explode and splatter themselves across the road in the manner of a zombie film fight scene.

Often on a climb there comes a point where you find a rhythm and forget about the physical exertion, and if that had happened I would have had my moment of satori right there and then. As it was, though, rather than enduring pain and suffering in order to achieve Zen enlightenment, here I never got beyond the pain and suffering part.

I stopped to catch my breath, eat my Smarties and mutter to myself, ‘Jesus fecking Christ this is steep!’ approximately fifteen times on the way up, and the only thing that prevented me from walking instead of riding was the fact that the last of the day’s hikers and sightseers were simultaneously on their way back down the mountain. The indignity of being seen pushing my bike along by its handlebars would have been too much to bear, so I gritted my teeth, fixed my gaze on the road ahead and strained to turn the pedals, in the hope that the procession of passersby would be impressed with my true-grit, true-Brit, never-say-die spirit of empire-building excellence.

Finally, after the best part of an hour and a half of torture, and just as I had switched on my lights to combat the encroaching gloom, first one car park and then another materialised – both now empty – and the road reached a dead end just below two radio transmitters, the Yamizo-miné shrine and this impressively castle-like observation tower.

By now the skies had clouded over and there wasn’t much to observe, although at one point a canvas-covered army truck drove up and three members of the jiéitai (自衛隊 / Japan’s self-defence force) dressed in full camouflage gear jumped out. They appeared to be looking for something – or perhaps someone – but after couple of minutes of running around and shouting orders at each other, gave up, got back in the truck and drove off again.

There was a patch of grass in the lee of the observation tower where I could have pitched my tent, but after a little more investigating I found that one of the sliding doors to this outbuilding had been left unlocked.

Inside there was a cubby hole at one end stocked with chairs, mattresses and even a heater, although I resolved not to use them as I didn’t want to make a nuisance of myself, and in any case, had made a point of bringing as much clothing and bedding as I could stuff into my panniers.

I parked my bike beneath the eaves before unloading it (I made sure to take off my shoes at the door, of course), and soon it was time to settle down for my evening meal – such as it was – of three rice balls, two bananas, a jam-filled bread roll, a bag of peanuts and a tomato.

One rather important thing was missing, though, and that was fluids.

As well as boasting one of the Bando-sanjusan-kasho (板東三十三カ所), thirty-three shrines in the Kanto area that form part of a 1300km pilgrimage, Yamizo is listed among the Meisui-hyakusen (名水百選), one hundred of the most attractive and well-preserved springs in the country. Assuming water would be plentiful, I therefore hadn’t bothered to bring any drinks with me, and set off with my water bottle to find Ginshohsui (銀性水 – literally ‘silver gender water’), the highest of Yamizo’s five springs.

Onii-san had lent me a miner’s helmet-style headlight, which illuminated a cone-shaped shaft of misty air before me as I walked, and a wooden sign told me that ginshohsui was just seventy metres away, although having expected to hear the sound of water gushing forth from the ground, I was greeted instead with silence.

There at a bend in the path was a shallow pool of water with a grey plastic drainpipe poking out from the hillside above it. It wasn’t so much a mountain spring as a murky puddle, and by the headlight I could see a beetle-like insect scuttle its way through the carpet of rotting leaves at the bottom – in other words, the water in the pool was just that little bit too stagnant to be trusted as drinkable.

Perhaps, I thought, the other four springs would be more gushing and geyser-like, but I didn’t fancy hiking even further downhill only to be similarly underwhelmed. More to the point, I didn’t fancy hiking all the way back up again on legs already fragile from the climb.

Looking and listening more closely, it became apparent that there was indeed a tiny amount of water trickling from the drainpipe, so if I was to avoid death by dehydration – well, OK, maybe not death, but certainly a further dose of pain and suffering – my only option was to sit here and wait as my water bottle filled.

Having positioned myself on a moss-covered rock at the edge of the pool, I realised that the water was flowing so slowly that rather than fall directly downwards, it was first of all snaking its way around the rim and back along the outside of the pipe, and that the sweet spot – that is to say the ideal position beneath which to hold my water bottle – wasn’t fixed, but moved ever so slightly depending on the subtlest variations in the flow of water. This meant that I had to keep as still and as quiet as possible, all the while listening for the dripping sound in the bottle: if the sound stopped I moved the bottle a smidgen one way or the other until it became audible again.

I was still thirsty from the climb, so at the first couple of attempts waited just a few minutes before gulping down whatever water had accumulated. Eventually, though, I decided that one full bottle – about 750ml – ought to be enough to see me through the night. I found a more comfortable position on a different but equally mossy rock, held out my right arm (it was at this point that I was thankful for my over-developed triceps, the result of years spent holding a boom pole with a microphone on the end of it for film and TV shoots), and since I didn’t want to waste the batteries, turned off my headlight.

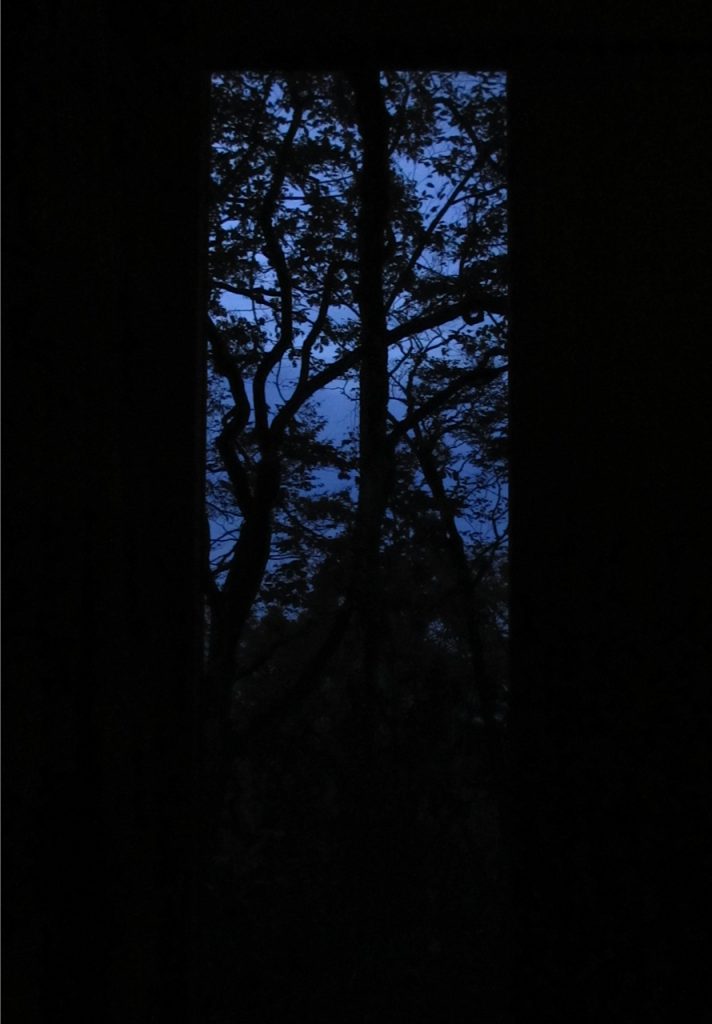

The trees’ swaying silhouettes were visible against the night sky, and their leaves rustled in the wind or crackled like crisp packets as they were blown along the forest floor. I listened for any sound that might be regular – the footsteps of a wild boar, for example, or even a domesticated hiker – but there was none. At one point I felt the tiniest movement of air as a bat flew past my face and circled the pool, its wings a blurred flash in the semi-darkness, but to all intents and purposes I was alone, and it occurred to me this was the most isolated I had been in my entire life, with no other human being within a radius of several kilometres.

So why am I here? I thought to myself. Why am I sitting on a rock in the freezing cold with my arm about to fall off from the strain of holding a water bottle beneath the trickle of water from a plastic drainpipe? Why am I about to spend the night on a lonely mountaintop, when I could be spending it in my living room, in front of the telly, before climbing into a hot bath and going to sleep on a fluffy futon beneath a warm duvet?

Why, for a holiday, of course!

OK, so this might not be most people’s idea of a holiday, and I had no luxuries to speak of: no bath, no shower, no TV, no heated toilet seat with bidet facility (although there was a small, basic toilet block next to the radio transmitters that despite the isolated location had been stocked with a fresh supply of toilet paper), no hot food, no hot water, and as it turned out, not much in the way of cold water, either.

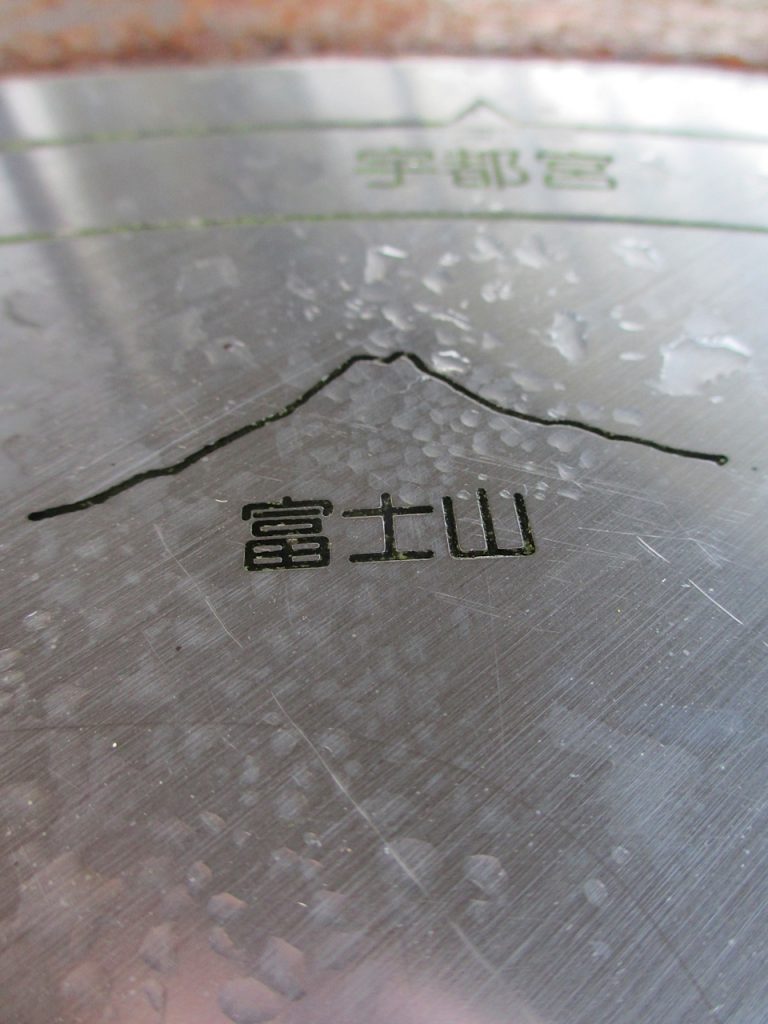

I was here for the challenge, I suppose, and for the view: as well as the sunrise and the surrounding countryside, with any luck I would get to see Mount Fuji – more than 200km distant – the following morning.

Then as the trees continued to sway in the breeze, the leaves continued to dance around the forest floor and the dripping sound changed in pitch as my water bottle gradually filled, I once more thought to myself, why am I here? Except this time it was in the larger, philosophical, Capital Letters, Why Am I Here and What Is The Meaning Of Life? sense.

In my previous capacity as someone who held a boom pole with a microphone on the end of it for a living, I spent many happy hours driving around the UK in vans full of camera equipment, usually with a fellow technician or two to keep me company, and one particular conversation – which took place, if my memory serves me correctly, on the A13 just outside Southend – stuck in my mind.

Myself and the camera assistant were somewhere in our late twenties, while the cameraman was somewhere in his early forties, and after listening to us talking about our lives for a while, he chipped in.

‘I know what it’s like,’ he said. ‘You’re working in showbiz, you go to some pretty nice places and meet some pretty glamorous people. You’re earning a bit of money, you’ve got your flat in London, your Ikea furniture, a big TV and a nice stereo system. You go to the pub with your mates and you go to the cinema to watch a movie. You think you’re pretty happy, don’t you? I mean, you think you’ve got it sorted.’

The assistant and I looked at each other with smiles of recognition.

‘Yep,’ I said. ‘As it happens you’ve just described my life.’

‘How did you know?’ said the camera assistant.

‘Because I was like that myself once. But eventually I decided that I needed to settle down. I found someone nice, got married and had kids. And kids,’ said the cameraman, ‘are the missing piece of the puzzle.’

In actual fact I had always suspected this to be the case, and even when I was young and found the prospect of having children utterly terrifying, deep down I somehow instinctively knew that one day I would change my mind, or perhaps just accidentally start a family and realise that it wasn’t such a hideous ordeal after all. It wasn’t until I became a father, though, that I truly understood what my colleague was talking about, although this, too, was as much to do with finding someone who was willing to be the mother of my children, rather than with deciding that I wanted to have them in the first place.

Bringing up M Jr is by turns miraculous, and inspiring, and uplifting, not to mention exhausting (a couple of weeks ago all three of us came down with the norovirus, and one particular night turned into a kind of three-person toilet relay of vomiting and diarrhea).

Witnessing one human being’s journey practically from conception onwards is akin to witnessing the evolution of the entire human race in microcosm. You see them in the womb when they are barely more than a pixel on a computer screen, and, like some pre-historic sea creature, yet to set foot on dry land (this, incidentally, is one of the most infinitely mysterious things about babies, in that they are first of all amphibious, inhaling amniotic fluid as if through a set of gills, and only transform into air-breathing mammals when they are halfway out of the womb). You hear their heartbeat and watch as their limbs and features develop, and then once they emerge you feel the grip of their hand on your finger, and watch them sleep and eat and pee and poo and cry and smile for the very first time.

In evolutionary terms, M Jr is currently at the caveman stage – or should I say cavegirl – in the sense that she is standing on her hind legs, using rudimentary language, gestures and tools. She hasn’t yet started a fire, invented the wheel or written the complete works of Shakespeare, but that will all happen in due course. In the meantime she can already listen, learn, watch, copy, remember, emote, give and receive affection, accept or refuse requests, ask and answer questions. All human life and all of human history has somehow been distilled into this one, tiny being with a wobbly walk and a voice like a slightly less robotic version of R2D2’s, and in this sense just one of its members embodies the hopes and fears of the human race as a whole.

All of which contemplation brought me back round to my original, literal, lower-case question, namely, why am I here? If my wife, daughter and unborn son are so important to me, why am I sitting on a mossy rock, on a cold mountaintop, in near darkness, waiting for a water bottle to fill very, very slowly, before sleeping on my own in a bare outbuilding, with not another living soul for miles around? And asking the question like that made it a little more difficult to answer.

I suppose everyone, to coin a phrase, needs a break from time to time, and even though I love being with my family, I also happen to enjoy being on my own. Cycle tours, however long or short, are my way of doing this, what is referred to in Japanese as kibuntenkan (気分転換), a change of scene. Recently, for example, Mrs M has been putting M Jr in a nursery a couple of times a week, not just because she is tired from being pregnant and looking after a one year old, but because she wants to have some time in her life when she is something other than ‘just’ a mother.

OK, so maybe this is just my excuse for being a good-for-nothing, layabout husband; maybe all of that Meaning Of Life stuff is a bit over the top, and maybe I really was just sitting on a rock waiting for a water bottle to fill, nothing deeper or more meaningful than that. But regardless, there was something meditative about the experience, and by that point any anxiety I had at the prospect of spending the night cold and alone had dissipated.

I couldn’t tell you exactly how long I had been there – probably no more than thirty or forty minutes – but eventually I realised that the dripping noise had stopped, and when I poked a finger into the mouth of my water bottle, that it had filled to overflowing.

In exactly the same way that it is possible, on a long climb, to get into such a rhythm that you zone out and forget you are turning the pedals at all, so I had ceased to be concerned about how long it was going to take for the bottle to fill, and ceased to listen for the change in pitch in the sound of the dripping water as it did so. Rested, enlightened and saved from dehydration, I screwed the cap back on my water bottle, switched on my headlight and walked back to the summit of Mount Yamizo to have dinner.

I had planned to call Mrs M and tell her how I was getting on, but there was no signal on my mobile phone and even an email I tried to send didn’t make it through the ether, so once I had eaten, all I had to keep me company was a single comic book.

Upon discovering that I was a fan of Japanese manga, a deputy headmaster at one of the schools where I teach suggested that I read one of the classics, namely Hi-no-tori (火の鳥 / The Phoenix) by Osamu Tezuka. Tezuka is described in Wikipedia as the ‘god of manga’, and Hi-no-tori as his ‘life’s work’, and it tells the story of a phoenix which is said to grant eternal life to anyone who can capture it and drink its blood.

Having read the first of its twelve volumes, I cannot recommend it highly enough, and what follows is my translation of a scene I read that night. In it, the young huntsman Nagi has tracked the Phoenix to the volcano where it nests, and just as he is about to begin firing arrows at it, hears the firebird’s voice in his head.

Nagi: Why is it you’re the only one that gets to live forever, while all of us humans have to die? That’s so unfair!

Phoenix: Unfair, you say? What are you hoping for? The power to avoid death? Or would you rather have good fortune while you’re still alive?

Nagi: I don’t give a damn about good fortune! But if I can live forever like you, that’s good fortune, isn’t it?

Phoenix: Look down at your feet, Nagi. Can you see the ants? They’re alive, aren’t they? And they live for just six months. The life of a mayfly is shorter still. Even if a mayfly reproduces, it lives for just three days. Nobody calls that bad fortune, though.

Nagi: So what does a stupid little insect know that we don’t?

Phoenix: The lifetime of an insect may be ordained by nature, but they are brought up properly, they eat, they love each other, they give birth to their young, they are fulfilled, and then they die. Human beings live longer than the insects, longer than the fish in the sea, longer than dogs and cats and monkeys. In the course of a lifetime, if you can find happiness, isn’t that good fortune enough?

Nagi: You’re not making any sense! And anyway, I’m going to shoot you down.

Phoenix: Whether or not you understand, Nagi, you will still die one day.

Nagi: Before I do, I’ll be sure to drink your blood!

I’m not ashamed to say that I went to sleep that night with tears in my eyes, because as I read Hi-no-tori, I realised that I have found happiness in my life, and this is as much as I can ask for. My alarm woke me at five-thirty the next morning, and I packed up my belongings as quickly as I could – the sun was due to rise at six – before stepping outside.

I had been alone for almost exactly twelve hours when an early-morning sightseer joined me in the observation tower, and we lamented the fact that even on such a fine day, this was as close as we would get to seeing Mount Fuji.

Then at about seven-thirty I threw a coin in the collection box at Yamizo-miné shrine and prayed that my children will grow up happy and healthy, before drinking the remainder of my precious spring water and freewheeling my way back down the mountain.

What a fantastic post. It had everything – solitude, physical exertion, nature and the cerebral. A really enjoyable read!

I am going to give hinotori a go now as well.

The freewheel down must have been ace…

Hi Shikaishi

Thanks very much for your comment and I’m glad you enjoyed the post.

The freewheel down was indeed great – when I’m coming back down a mountain I’m always torn between wanting to ride as quickly as I can and wanting to stop and take in the view. This time I kind of compromised between the two, so the photos at the beginning of the post of the torii, the cherub and the hairpin bend were actually taken in the morning on my way down and not in the evening on my way up.

Hi No Tori is like nothing I’ve ever read – it veers between comedy, tragedy, the spiritual and the banal, but is all the better for it. It’s also, I have to say, quite hard to find – I got the first part for a couple of hundred yen in a second-hand comic shop, but haven’t managed to track down part 2 yet, so may have to resort to buying it on Amazon…

Funny the way life comes into focus with children, hard-hearted Tiverton cynicism notwithstanding. When you get bored of taking your bicycle and seeking transcendence in Japan, bring it to the Forest of Dean. Not so many mountains (or rice balls), but a good chippy and lots of other cyclists and bike-trails. Give my love to Mrs M and I hope her final couple of weeks of pregnancy are not too sleep-deprived.

A good chippy? I’m on my way to the airport now!