Way back in January 2011, one of the very first posts on this blog was about the writer Alan Booth, who lived here for more than two decades, produced two of the most well known and well liked travel books about Japan, and sadly passed away at the age of just 46. Little did I know at the time, but that post would become by far the most popular that I ever wrote – on a very small scale indeed, you might almost describe it as ‘buzzy’.

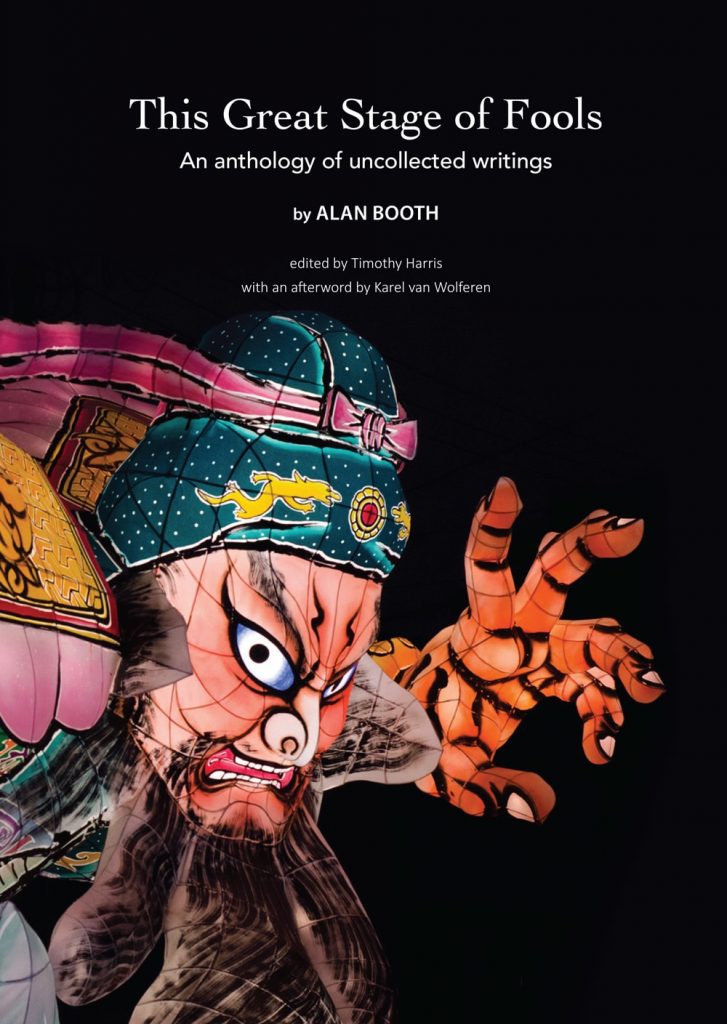

Comments on it became, in a quite spontaneous way, a kind of unofficial noticeboard for fans – and even acquaintances – of Booth, in large part because the post’s popularity happened to coincide with the creation of This Great Stage of Fools, a book of his hitherto uncollected and unpublished writing. This Great Stage of Fools was compiled and edited – lovingly, painstakingly and over the course of several years – by Booth’s friend Timothy Harris, who himself was one of the commenters, and who was considerate enough to keep us up to date regarding progress on the book, from his trawling through the archives all the way to the publication party in May of last year (of which more later).

It took me a while to get round to buying a copy of This Great Stage of Fools, it took a while to get round to reading it, and it has taken another long while to get round to writing this review, and partly because I realised that I had so much to say on the subject, partly because this is the first post on Muzuhashi for the best part of three years, please forgive me if I ramble on for an unnecessarily long time, and wander down one or two side roads along the way. I use the quite selfish and thoroughly presumptuous excuse that Booth himself would have approved.

I first saw Alan Booth’s name mentioned in Will Ferguson’s Hokkaido Highway Blues, which despite – or perhaps even because of – its unexpectedly gloomy ending, and along with Booth’s own books, Donald Richie’s The Inland Sea and Leslie Downer’s On the Narrow Road to the Deep North, is one of my favourite about Japan.

As Ferguson is travelling through Hokkaido on the final stage of his hitchhiking odyssey, he stays in a guest house whose proprietors suggest to a star-struck Ferguson that Booth, too, may have stayed there while he was walking in the opposite direction, a decade or two previously, and having just embarked on his own top-to-tail journey through Japan.

Thanks to this I discovered Booth, and had soon read both of his books, before eventually writing a review of the second – Looking for the Lost, which is also, I should mention here, the result of the efforts and editing prowess of Timothy Harris – that became the aforementioned Alan Booth blog entry.

Slowly but surely, as I was blogging about Japan, settling into life here (for the second time – I lived in Tokyo and then Ibaraki for two years in the mid-noughties) and becoming a father to Muzuhashi Juniors I and II, readers began to respond to the post, and in reply to a comment along the lines of, ‘I wish there was another collection of Booth’s writing out there,’ Harris himself appeared to say that yes, there was, and that he was the editor.

Along with Harris, his publisher Ry Beville, and even friends of Booth’s from his university days, all sorts of other fans chipped in to the discussion. I learned of Fexluz’s epic plan to re-walk the entire journey described in The Roads to Sata – including, wherever possible, staying in the same lodgings and sticking to the same schedule – and was fortunate enough to become acquainted with the very nice people behind the Alan Booth Appreciation Facebook page. Then, at long last, came This Great Stage of Fools.

Speaking of which – and before I continue – a quick commercial break: if you’re a fan of Booth’s, or of this blog, or if you’re a Japanophile who just happened to drop by, you can purchase a copy of This Great Stage of Fools direct from the Bright Wave Media website for 3000 yen including delivery (3500 if you live outside Japan). As Timothy explained to me, dealing with Amazon can be a financially disadvantageous experience for small-scale publishers of non-best sellers, because they are obliged to charge less than is necessary to turn a profit. So think of the slightly-above-average price tag – along with the mild inconvenience of not being able to use Amazon Prime etc. – as your contribution to keeping writers like Booth in the spotlight, and editors like Harris and publishers like Bright Wave in an honest living.

But anyway, when I finally sat down (or rather, lay down beneath the kotatsu in our front room) to read This Great Stage of Fools, I have to confess that my first thoughts were somewhat equivocal.

The collection starts with more than a hundred pages of Booth’s film reviews for the Asahi Newspaper, ranging from those poking fun at creatively bankrupt box office hits, to those heaping praise on what would nowadays be described as ‘art house’ films. Booth’s reviews are, as you might expect, insightful, well written and at times very amusing, and he was clearly knowledgeable about Japanese film history. Of the films he reviews, however, I have seen just four (Ran, Grave of the Fireflies, Akira and Kiki’s Delivery Service), heard of just three more, and even if I was inspired by his reviews to see more, the majority would not be easy to track down, even here in Japan.

So much as I admired the film reviews, to me they were rather abstract, and as I read my way through them, I couldn’t help but think that Harris had compiled This Great Stage of Fools in the wrong order, for as any music fan knows, the basic principle when deciding the running order of an album is to put the hits at the beginning, while here he seemed to be starting with the obscurities, B-sides and bonus tracks.

The second, third and fourth sections of the book are much more the kind of thing we have come to expect from Booth, being a combination of eyewitness accounts of Japanese festivals, essays about folk songs which aren’t a million miles away from being travel pieces themselves, a biography of the shamisen player Chikuzan Takahashi – whose birthplace, the Tsugaru Peninsula in Aomori Prefecture, might reasonably be described as Booth’s spiritual home – and an account of a walk across Shikoku.

The latter was commissioned by the Japan Airlines magazine Winds, and makes for a satisfying addition to The Roads to Sata, being nothing more pretentious than a day-by-day diary, with descriptions of the people he meets, the places he stays and the toenails he loses along the way. I wonder if he had planned to flesh it out at some point with some historical, cultural and geographical detail, although it also made me feel sad that Booth never walked the Henro Pilgrimage around 88 of Shikoku’s shrines, which would have been the ideal subject for one of his travel books.

(Parenthetically, I have myself crossed the Minokoshi Pass below Mt. Tsurugi in Shikoku – where Booth gets into a drunken karaoke battle with a fellow diner – and by that point the village just below it was home to an art installation that makes a very telling point about the decrease in number and increase in average age of the Japanese, and about their seemingly inexorable movement from rural to urban centres of population.)

So with its sketches of local people and unusual goings on, its dancing, devils, myths and legends, the middle section of This Great Stage of Fools is reassuringly familiar, but it is in section five – entitled Going Hence – that Harris’s reasons for ordering the book as he did become apparent.

For the end of This Great Stage of Fools is about Booth’s end – in both senses of the word, in fact, as his terminal illness originated in his colon, and probably the funniest passage in the book is his account of two visits to Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital, the first of which involves a nurse taking a stool sample with only a curtained screen separating them from a hundred or so other people in the waiting room, and the second a doctor questioning him about his bowel movements as a similarly inquisitive queue of patients sits within earshot.

Indeed, Booth’s humour here is as dry as a half-litre bottle of Asahi, and while for the most part Going Hence is either played for laughs or avoids sentimentality and self-pity, one can only imagine the pain – both physical and psychological – that Booth was going through at the time.

So the writing in This Great Stage of Fools becomes more personal as it progresses, and therefore better and better, and the more I read, the more I realised that the only possible place for an account of Booth’s final days would be in the final pages of the collection. And for that reason, to put the film reviews after this, or to shuffle them with the travel and cultural pieces, would never work.

In any case, an insight into Booth’s illness was what I had wanted to read more than anything else, ever since his brief reference to it on the final page of Looking for the Lost. But why should that be so? Well, I suppose to myself and many other Japanophiles, Booth is a hero of sorts, and because of his untimely death – the details of which most of us were until now entirely ignorant – he has the allure of a kind of gaijin James Dean: someone who lived fast, died young and left a good-looking corpse. Well, OK, so it was more like living within the speed limit, dying in middle-age and leaving a ruddily-complexioned, British-looking corpse, but whereas Booth’s death was in no way glamorous, the very fact that it happened lent him an air of mystery that writers like Will Ferguson, Donald Richie or Leslie Downer, for example (and with apologies to all three), do not have.

And more than that, while I abhor the whole concept of celebrity culture – or as it’s referred to here in Japan, geinohkai (芸能界 / げいのうかい) – I can’t help but be curious about the personal life of the people I admire. So while Booth doesn’t appear to have been someone who made any particular effort to keep his private life hidden, there is something rather thrilling, and at the same time cathartic, about reading the final section of This Great Stage of Fools, because we have at long last been granted a glimpse of the human being behind the books that we love. (Again parenthetically: it is interesting to note that even in an era that pre-dated the instant communication of the internet, Booth received his fair share of hate mail in the form of handwritten letters.)

But for me at least, it is not just these things that make This Great Stage of Fools so important, and by way of explanation, you will have to allow me to wander off along one of those side roads I was talking about at the beginning of this post.

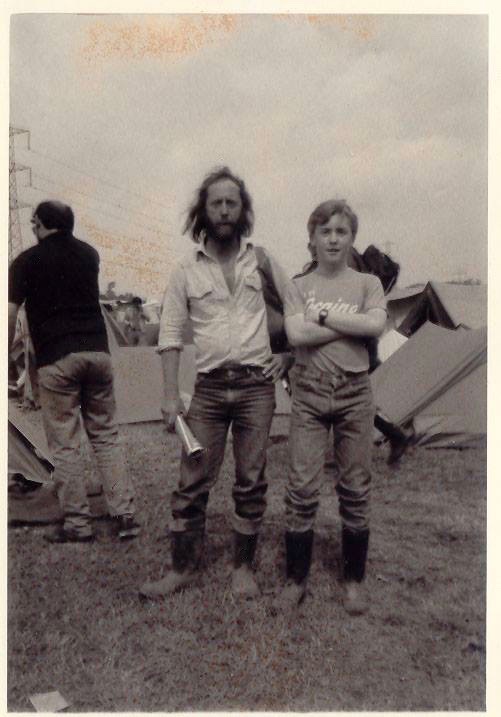

My father was born into a wealthy family and went to a reputable public school (Charterhouse, no less – the Alma Mater of people like Robert Baden Powell, David Dimbleby, Peter Gabriel and, er, Jeremy Hunt), but essentially dropped out of the system at eighteen, finding employment in a succession of part-time and temporary jobs. When he met my mother he was running secondhand bookshop in Bristol, and after they separated he instead travelled the country as a member of the Provincial Booksellers Fairs Association. He was also – like his father before him, and as I would subsequently become – an aspiring (i.e. failed) writer, and while I have yet to find the time to decipher his practically illegible handwriting, at one point wrote a full-length autobiography, as well as a good deal of romantic poetry (that is in the romantic tradition, as opposed to the lovey-dovey one). In the late eighties he decided to quit the bookselling and go back to school, securing a place at the now defunct Coleg Harlech in west Wales, and while he did, as far as I can remember, complete the course and have ambitions of becoming a university lecturer, this coincided with his diagnosis with skin cancer.

Although he didn’t fill me in on many of the details, it would seem that he contracted the disease while on a walking holiday in the south of France, and by the time he went to have a mole which had appeared on face looked at by a doctor, the cancer had already spread too far for there to be any hope of a cure. After an operation to remove tumours in his neck and shoulder, a round or two of chemotherapy (which he described as ‘like having malaria’), and a rather desperate (desperate for him because it was so out of character) attempt at a kind of detox diet cancer treatment, he passed away in the summer of 1990.

Because my parents separated when I was about four years old, I didn’t see much of my father. He travelled around a lot and even when he was nearby, sometimes preferred not to visit because his relationship with my mother could be rather strained. At the end of his life, too, he was living a long way away, and by that point I was a miserable teenager who rarely left the house and wanted to have as little to do with my parents as possible. So while I was upset when I learned of his death and did of course go to the funeral, I’m not sure that I ever properly grieved for him.

Cut to about twenty-five years later, and I was given a batch of mp3 files by my brother, digitised from some dictaphone tapes which had been languishing in the attic at our mother’s house. The tapes were recorded by my father on the aforementioned walking tour (actually tours – as it turns out he went on two, in successive summers in the late eighties), and my brother recommended that I listen to them.

I had been aware of the tapes’ existence from the time my father died, but even once the recordings were in my iTunes library, was hesitant to listen to them. There were various reasons for this, the main one being that the experience could turn into a kind of morbid pantomime, with myself as the audience urging him – in vain and unheard – to use some sunblock or buy a bigger hat, as he – oblivious to his fate – mentioned how hot and sunny it was.

Then, about two and a half years ago, I fell ill myself. This was no terminal illness, and unlike Alan Booth, for example, I wasn’t given a 30% chance of five years to live. I didn’t even necessarily need to see a doctor (although I did consult several), let alone have chemotherapy, an operation, or a rectal examination within earshot of a room full of fellow patients. But it did count as a kind of mid-life crisis, and for a while at least, turned my entire life upside down, cause me to re-examine what that life really meant, and to quite fundamentally change me as a human being.

So while this is my first post to muzuhashi.com since 2016, the not-so-gory details of my illness can be found here, here, here and here, in a series of guest posts that James at the ALT Insider blog was kind enough to carry – probably the most I have written on any subject in that entire time.

But anyway, one of many new things I began doing in order to recover from my illness was to take a walk every evening after the children had gone to bed, and after a year of doing so with just my own thoughts for company, I dug out my headphones and started listening to music, podcasts and audio books. This eventually led me to my father’s recordings, and what I found in them was, in its own rather understated way, a revelation.

During the two walking holidays, whenever my father had something interesting to say, and sometimes when he was simply making his way along a footpath or a road, he would press the record button on his dictaphone. He talked about the scenery, the weather, the food he had eaten, where he had been and where he was going, and he also talked about himself. About how motivated, lazy, positive, negative, wide awake or worn out he was, and about his life: his work, his plans to go back into education, and his relationship with my brother and I.

So not only was this a voice I had not heard for nearly thirty years, it was also expounding on topics that even at the time I didn’t hear him talk about. At various points in the recordings he wonders how my brother and I are doing, reminisces about things that happened when we were growing up, and confesses that he would like to see us more. He also describes his regret at having wasted so much time worrying about his relationships, both with my mother and with subsequent girlfriends (apart from the woman he was living with when he died, these were women I had absolutely no idea existed during his lifetime, and while I believe I may have met one or two, they were never introduced to me as such).

Occasionally my father also recorded himself in conversation, and while he doesn’t appear to have been a fluent French speaker, he knew enough, as the saying goes, to get by. This was another aspect of his life that I had no real knowledge of, and particularly fascinating because it made me realise how I must sound when I speak – and struggle – with Japanese, both literally in the sense that our voices are similar, and conceptually in the sense that we both put ourselves in a position where we had to use a foreign language on the natives.

At one point in the recordings, he leaves the dictaphone running while using a hotel pay phone, and as I listened it took me a minute or two to realise that the person on the other end of the line was me. At the time I was sixteen, and had just arrived back from a school exchange visit to Hungary (which as it happened was emotionally tumultuous, and my first real brush with the depression that reappeared during my more recent illness). The conversation is fairly mundane, as we share travellers’ tales and he tells me when he expects to be back in the UK, and towards the end of the call he refers to me by a nickname that I had no memory of him using (no, not Muzuhashi, in case you were wondering).

In the background of the recordings, too, you can hear the sounds my father heard as he made his way through the south of France: tractors, passing cars, church bells, birdsong, buskers, and a group of customers singing what appears to be a rousing rugby song in a bar in Marseille. You can also hear his breathing and his footsteps, and as I walked the backstreets of small-town Ibaraki at nine or ten in the evening, these synchronised with my own, and this recording of the past was overlaid with the present moment of my own experience, my father’s words and my own thoughts about them overlapping, intermingling, and reverberating back and forth across the decades.

My father does indeed refer to the heat – to the sunshine, his sensitive skin, and how there is a patch of sunburn on his forehead that won’t heal up – and part of me wanted to call out to him, to warn him of the dangers, and to urge him to see a doctor sooner than he did, so that his life might instead be saved, and our relationship able to grow and develop; that he might still be with us today, and interested in my own adventure abroad.

But more than anything else, listening to the tapes was miraculous, because apart from one or two home videos, they are the only place in which his voice is preserved, and even though the mp3 files had been sitting in my iTunes library for the best part of a decade, hearing his voice again so unexpectedly was joyful, fascinating, moving, mysterious, and so many other things all at the same time.

At the time I listened to the recordings I was seeing (well, having video chats with on Skype) a psychotherapist, and relating to her the experience of hearing my father’s voice again, and of finding out so much that was new to me about his life and the way that he felt, brought my sessions with her to a natural and satisfying conclusion. It gave me the motivation I needed to move on with my life: not quite cured, but with a sense that the illness I had been dealing with for so long was fading into the background. And while it is somewhat of an exaggeration, reading This Great Stage of Fools – and in particular its final section – was a similar experience: revelatory because it was one that I never thought I would be granted.

Both Booth and my father died in their late forties from cancer that was diagnosed too late, and while their journeys through life were very different, both shared a passion for walking and a passion for words, so that for me, and if only in a small way, Booth is a father figure, and I realise now that one of the reasons I like his writing – and one of the reasons, no doubt, that my review of one of his books resonated so much with readers of this blog – is precisely because of this, so that when I wrote about Booth, I was also writing about my father, and about myself.

Booth’s words in the final section of This Great Stage of Fools are both personal and emotional, and as well as mentioning his family for the first time, he recounts a visit to India during which he spent time volunteering for Mother Theresa and the Missionaries of Charity.

Here Booth washes blankets in the appalling conditions of the Nirmal Hriday Hospice for terminally ill destitutes, and becomes a kind of surrogate father to patients at the Shishu Bhavan children’s hospital. What he describes is quite unlike the boozy, breezy bar chats of The Roads to Sata or Looking for the Lost, and in doing so, he reveals himself to be both compassionate and selfless. In the context of what was to come, one might also suggest that the experience prepared him for the suffering that was about to intrude into his life, and bestowed on him the humility he would need to confront his own mortality.

I recently read a manga by Yoko Takahashi called Gaikokujin no Daigimon (外国人の大疑問 / The Big Questions for Foreigners), which among other things contains the results of a questionnaire given to expats. In answer to the question, ‘What do you dislike about Japan?’ as well as such responses as, ‘Rush hour trains full of people’ and ‘The rent is expensive’, some people said, ‘Japan is very convenient, but for some reason I feel lonely.’ This is a sentiment to which I am sure a lot of expats can relate, and while in Going Hence Booth navigates his way through terminal cancer with the usual articulacy and good humour, for the first time in his writing, I sensed that he, too, may have been lonely living in Japan.

I wonder if Booth’s prodigious drinking was one way in which he dealt with this, and another reason I am drawn to his writing is because my father, too, was a drinker. But while my father was an alcoholic – in the sense that his personality changed for the worse when he drank – Booth really did appear to be a social drinker, and rather than alcohol being something that held him back, it enabled him to meet a huge variety of people, to communicate with them (often in Japanese, of course), and to pass on what he learned from them to his readers.

This Great Stage of Fools will almost certainly be the final published work by Booth, although there would appear to be even more writing of his that is yet to be collected. For example, one of the comments on my first Alan Booth post mentioned a travel piece for which Booth ‘went “undercover” on a Hato Tour Bus, seeing the sights of Tokyo with a group of other foreigners,’ which I for one would love to read, and his wife Su-Chzeng has an archive of his papers that will hopefully find a home in a university library or similar.

Both Su-Chzeng and Mirai – her daughter with Booth – spoke at the launch party for This Great Stage of Fools, and while I was unable to attend in person, I listened to Fexluz’s audio recording of the party on one of my evening walks. Alongside many wonderful tributes to and recollections of Booth, Mirai brings an unexpected new perspective to her reading of a passage from This Great Stage of Fools, investing her father’s words with drama, vivacity, and a quite different sense of humour from that which comes across on the page. Listening to this made me see Booth’s writing in a new light, and it heartens me to think that while Booth is no longer with us, his spirit lives on in his books, which will surely be read, enjoyed and reinterpreted for many years to come.