In the final week of the summer holidays, I spent two days with a friend of mine from the UK, Mr Brighton, who was in Japan on business. Aspects of his job – or rather, of his workplace and his employers – are top secret, so I won’t be able to divulge everything that we spoke about, but I will be able to tell you what we did, and at least some of the fascinating stories that he told me.

Mr Brighton is a member of Her Majesty’s…sorry, His Majesty’s Armed Forces, although he is not a highly trained killing machine on the frontline. Rather, he is a doctor, which would be interesting enough if it wasn’t for the fact that he didn’t become a doctor until he was middle-aged – or as we agreed to refer to it while we were together, kind of an in-between, late-early, semi-middle age (basically, we’re both in denial about the fact that we’re already old gits). He left school at 16 with just one O-level – i.e. the prehistoric version of a GCSE – and even having returned to further education, only added a solitary A-level. Very much like me, he had various part-time jobs before eventually getting a place at university, which I suppose is when we first met, although we did not know each other well and our social circles only overlapped in a small way. While I was studying film and photography, he was a year above me and majored in a subject that I didn’t even realise our university had offered. Having graduated, he worked in web design and other media-related niches. As he himself admitted, he never made it big, and even in his thirties, didn’t earn particularly large amounts of money and lived in fairly insalubrious house- and flat-shares. Even so, he still managed to indulge in his fair share of partying, and embarked on various adventures that included a Land’s End-to-John o’ Groats bicycle ride and an epic motorbike trip from the UK to Calcutta.

He met his partner around the time he left university and they have been together ever since. In their mid-thirties, when they were thinking of starting a family, Mr Brighton had what you might call a road-to-Calcutta moment. He decided to knuckle down and get a ‘proper’ job, perhaps realising that if he was to support a family and continue working as he approached in-between, late-early, semi-middle age, a more reliable and profitable source of income might be a good idea. With almost no previous experience apart from a job as a carer in a home for the disabled, he decided to become a doctor, and incredibly, after returning to further education to sit some science-y A-levels, proceeding to medical school, and beyond that to becoming a junior doctor, he realised his ambition within the space of about five years.

Having worked as a GP in the NHS, family doctor sense of the acronym, an old friend from his school days suggested that he try for a job in the armed forces, and since then – despite occasionally finding himself in conflict with his liberal sensibilities about the concept of working for the war machine, as it were – he has led a life of considerable adventure and variety. Among other things, this has involved spending several months on a submarine (pretty much everyone in a group photo that he showed me from that particular assignment had grown a very big beard) and piloting a Red Arrow. He has also ridden in a centrifuge: one of those machines that appeared in a James Bond film many years ago, the purpose of which is to test the subject’s ability to withstand ever increasing levels of g-force. As I may have explained before in this blog, I have practically zero tolerance to the most negligible levels of g-force, and feel queasy even after being spun around a few times with a blindfold on for a game of pin the tail on the donkey. Mr Brighton, on the other hand, emerged unscathed and fully conscious having been subjected to something like 8 or 9 g. As such, and if he ever decides on another career change, he may be suited to becoming an astronaut.

I always look forward to the rare occasions when friends, relatives, or acquaintances from the UK visit Japan in person, so I was pleasantly surprised to receive a message from Mr Brighton suggesting that we meet up this summer. Our initial plan was to go cycling in the countryside – potentially at this paradise of hairpin bends in Nikko, Tochigi Prefecture – but the practicalities of both of us making it to such an out-of-the-way location with our respective bicycles proved too difficult to overcome, and we settled instead on the idea of pootling around Tokyo on rental bikes. This was all very well in theory, but in practice – and despite successfully downloading the Hello Cycling app and inputting my credit card details – having met at Ueno Station on a Monday morning, try as I might and contrary to the information on the Hello Cycling FAQ page, it did not appear to be possible to hire two bicycles at the same time. But this proved to be fortuitous, in the sense that rather than cycling on the busy streets of Tokyo, we instead walked, talked, walked some more and talked some more, to the point that by the time we retired to our respective hotels at about seven in the evening, my Garmin told me that I had completed almost 30,000 steps.

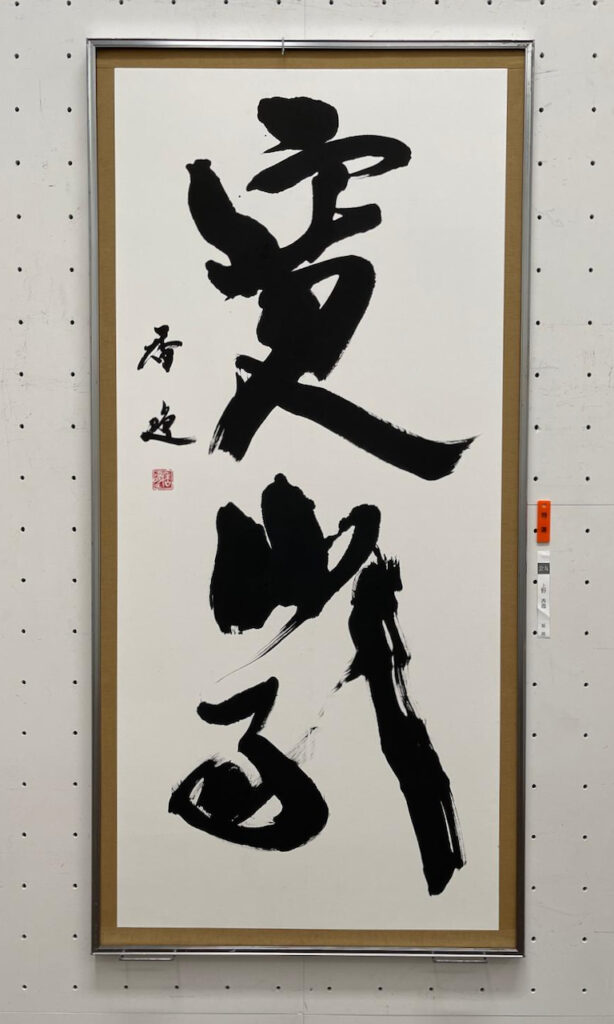

From Ueno we went to the Ameyoko street market, where the stallholders were still preparing for the day ahead, to the Tokyo National Museum in Ueno Park to peruse a calligraphy exhibition, where Mr Brighton couldn’t understand any of the exhibits because he has next-to-no knowledge of Japanese and I couldn’t understand most of the exhibits because the calligraphy was so stylised as to be practically incomprehensible even for a translator, and to a Showa-era shopping street called Yanaka Ginza, where we bypassed somewhere called Fuku Bagel (in this case, the word fuku has neither the pronunciation nor the meaning that you might expect) in favour of lunch at a trendy little café whose speciality was mochi (rice cakes).

Mr Brighton was keen to sample new and interesting foods and this seemed like a good way to start our culinary adventure. I ordered kinako (roasted soybean flour) mochi with a kind of brown sugar syrup, he ordered grated daikon (Japanese radish, aka mooli) mochi with spring onions, and both were delicious, if a little – nay, a lot – on the sticky side. Fortuitously, we found a secondhand kimono shop on the same street, where Mr Brighton bought a yukata (light, summer kimono) for his partner at the bargain-basement price of less than ¥2,000.

Among the places he had suggested visiting was Aoyama Cemetery, and as we later found out, there was an interesting coincidence involved in this choice. You see, Mr Brighton’s grandparents actually lived in Tokyo before World War II. His grandfather was a fluent Japanese speaker, worked as an interpreter, and during the war was recruited as a spy by the British intelligence services, continuing in the same profession for many years. Mr Brighton’s grandparents subsequently lived in a detached house in the sleepy UK suburbs and apparently, a helicopter would sometimes land on their front lawn. Mr Brighton’s grandfather would hop on board and disappear for several months, returning from some James Bond-style spy mission as if from a day working 9 to 5 at the local bank, with a breezy greeting and without being able to tell either his wife or anyone else what he had been doing.

Mr Brighton had a picture on his phone of some old black and white photographs in an album, showing the house somewhere in Tokyo where his grandparents had lived. In the harsh sunlight on a small screen, we couldn’t work out where they were taken, but a few days later, he took a closer look and saw the words ‘Kogai-cho, Azabu’ handwritten in the album. Azabu is now a very chic part of town and just a few minutes’ walk from Aoyama Cemetery, so in a sense, we made our pilgrimage without realising it. Oblivious to this at the time, instead of heading south towards Azabu, we headed northwest towards Shibuya and did the standard tourist thing of traversing Shibuya Scramble Crossing – five times, to be precise. On the way, we also popped in at an onigiri (rice ball) café. Onigiri are an everyday food in the manner the British sandwich, but this establishment charged a little more money for a slightly fancier version – delicious, but so fancy that they stuck to the wooden pedestals on which they were served and had to be forcibly scraped off with our chopsticks.

The temperature in Tokyo that day was apparently around 27°C, but oddly, walking around the various districts that we visited and punctuating our journey with air-conditioned pit stops meant that neither of us felt the heat as much as we had expected. We rounded off the day at Omoide Yokocho in Shinjuku, a narrow alleyway of eateries and drinkeries that may or may not have served as the model for one of the opening scenes in the film Blade Runner. At one point a few years back, Omoide Yokocho was in danger of being demolished and redeveloped as yet another faceless shopping mall, but fortunately, the powers that be realised that it was a valuable tourist attraction precisely because of how run down and rough at the edges it was, notwithstanding the fact that it’s also a blatant fire hazard, as a good proportion of the atmospherically cramped restaurants there serve yakitori – i.e. chicken cooked over open flame grills – and would be hard to vacate in an emergency.

From what I could see, around half of these restaurants were frequented by Japanese customers, while the other half targeted tourists like us. As a result, the service we received in the one that we chose was not up to the usual high standards. In fact, you could have said the same for the food, but fair-to-middling Japanese service and food are still far superior to pretty much anything in the UK, and there were tofu and vegetable dishes for me to enjoy while Mr Brighton chowed down on skin, gristle, and other indeterminate chicken parts.

Thank you for sharing this. While I haven’t made it to Tokyo, reading this brings back memories of similar days spent with friends from home who came to visit. Thanks for sharing the story about Omoide Yokocho!